An annotated bibliography is a list of sources (books, articles, websites, etc.) on a particular topic or related to a particular research question. What sets it apart from a regular bibliography is that a brief annotation follows each source.

Here is an example of an annotated bibliography entry for a book source:

Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The story of success. Little, Brown and Co.

In this book, Gladwell explores the factors that contribute to high levels of success. He challenges the assumption that successful people are solely a product of meritocracy, claiming that culture, circumstance, upbringing, and historical timing are also critical factors. Using case studies of outliers from various walks of life, such as business titans, athletes, entertainers, and computer programmers, Gladwell attempts to provide a revised perspective on what makes people achieve remarkable success. This book is highly relevant to my research on vocational pathways and creating environments conducive to success as it provides qualitative evidence that genius is not entirely inborn. Gladwell’s engaging storytelling makes his book both accessible and thought-provoking on issues of opportunity, cultural values, and redefining traditional notions of what drives success.

Annotated bibliography format: APA, MLA, Chicago

The format for an annotated bibliography can vary depending on the style guide used. Here are the three most common styles:

- APA

- MLA

- Chicago

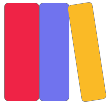

APA Style

When formatting an annotated bibliography in APA style, use double spacing throughout and align all text to the left margin. For the reference entry, apply a hanging indent where the first line is flush left and subsequent lines are indented (usually 0.5 inches).

The annotation immediately follows the reference entry on the next line. The annotation should maintain the same hanging indentation as the reference entry lines. If an annotation has multiple paragraphs, indent the first line of any new paragraphs an additional time beyond the hanging indent.

This structured use of hanging and additional indentation allows the reader to differentiate between the reference entry and the annotation paragraph(s) in the APA annotated bibliography format. Both components should remain double-spaced for readability.

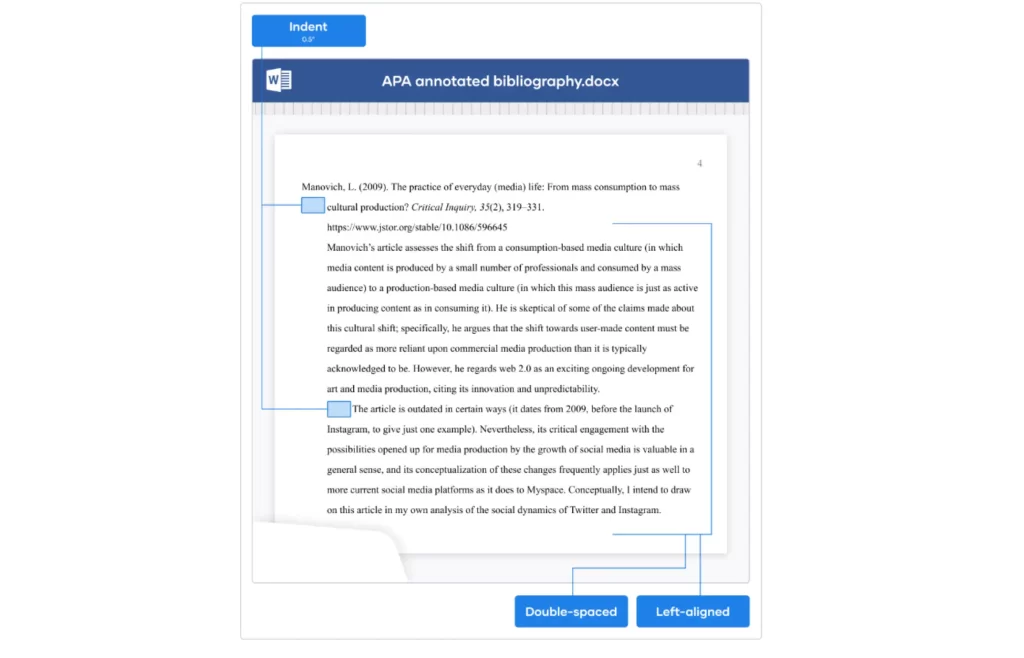

MLA style

For an annotated bibliography in MLA style, use double spacing consistently throughout the reference entry and annotation. All text should be aligned to the left margin. Apply a hanging indent to the Works Cited entry, having the second and subsequent lines indented (0.5 inches).

The annotation paragraph(s) should then be indented 1 inch from the left margin – twice as far as the hanging indent in the reference entry. If the annotation consists of two or more paragraphs, indent the first line of each new paragraph an additional 0.5 inches beyond the 1-inch annotation indent.

However, if the entire annotation is contained within a single paragraph, no additional indentation of the first line is needed beyond the 1-inch indent. This indentation scheme allows the reader to clearly distinguish the referenced source from the accompanying descriptive and evaluative annotation text in MLA format. Both components maintain left alignment and double spacing.

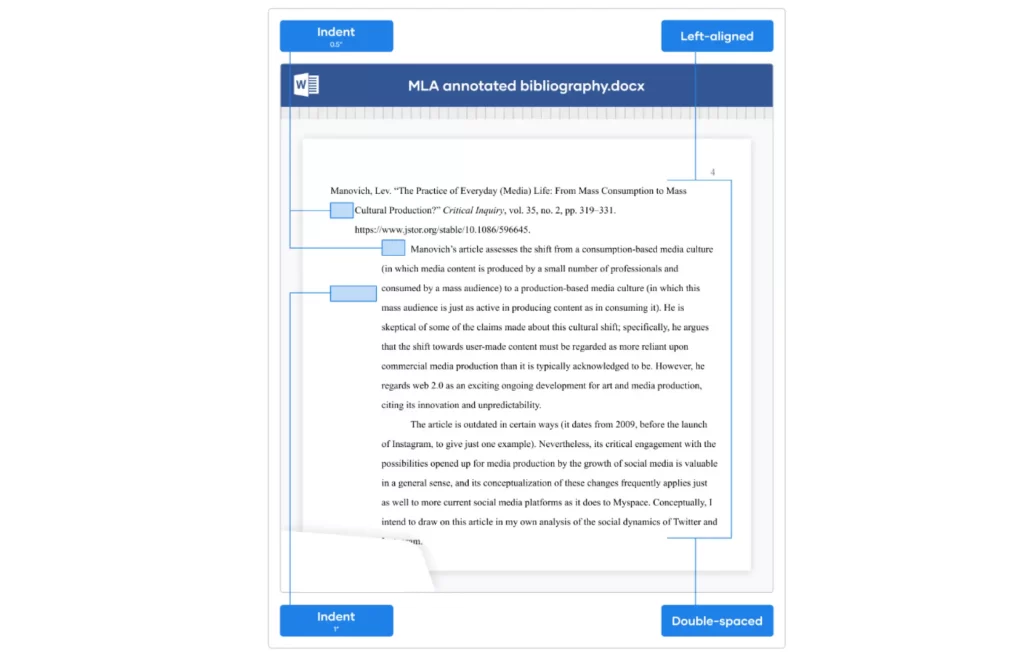

Chicago style

For the bibliography entry in Chicago style, use single spacing and a hanging indent where the first line is flush left and subsequent lines are indented (0.5 inches). However, the accompanying annotation should utilize indentation, double spacing, and left alignment. Indent the entire annotation so it lines up with the hanging indent lines of the bibliography entry above it.

Maintain double spacing between lines within the annotation. If the annotation consists of multiple paragraphs, indent the first line of each new paragraph an additional time beyond the initial indentation.

This formatting allows the single-spaced bibliography entry to be visually separated from the indented, double-spaced annotation paragraphs in keeping with Chicago style guidelines. The indentations and spacing cues clarify where the reference ends and the annotation begins for the reader.

How to write an annotated bibliography

Begin by generating a complete reference entry for each source, following the citation style specified for the assignment. This should include the author, title, date, and other relevant publication details.

The annotations are usually 50 to 200 words long and presented as a single paragraph. The precise length may vary depending on the word count requirements, each source’s relative importance and detail, and the total number of sources included.

Consult the assignment instructions or check with your instructor to determine the type of annotations they expect. This will help guide the content and focus of each annotation.

Descriptive annotations

Descriptive annotations provide a concise summary of the key points, arguments, and conclusions presented in a source. The goal is to give the reader a clear understanding of the source’s content and purpose without any evaluation.

Descriptive annotation example

Ripple, W. J., Wolf, C., Newsome, T. M., Barnard, P., & Moomaw, W. R. (2020). World scientists’ warning of a climate emergency. BioScience, 70(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biz088

This article presents a stark warning from over 11,000 scientists across 153 countries about the dire threat of climate change. The authors analyze multiple vital signs of environmental health, including greenhouse gas emissions, ocean temperatures, and deforestation rates, finding that the vast majority have continued to trend in the wrong direction despite decades of global climate negotiations and policy efforts. They call for urgent and large-scale actions, such as ending fossil fuel extraction and subsidies, restoring and protecting ecosystems, and shifting to plant-based diets to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C and avoid catastrophic climate impacts. The article serves as a powerful, data-driven rallying cry for immediate, coordinated action to address the climate crisis.

Evaluative annotations

Evaluative annotations go beyond describing a source’s content. They provide a critical analysis of the source’s strengths, weaknesses, biases, and overall quality. The annotation should assess the source’s credibility, reliability, and relevance to the research topic.

Evaluative annotation example

Solnit, R. (2017). The mother of all questions. Haymarket Books.

In this collection of essays, acclaimed writer Rebecca Solnit explores various topics related to gender, power, and social change. Drawing from her extensive background in feminism, history, and cultural criticism, Solnit offers insightful and often poetic reflections on issues such as the persistence of violence against women, the erosion of reproductive rights, and the importance of recognizing women’s contributions to social movements. While Solnit’s left-leaning political views are evident throughout the book, she backs up her arguments with well-researched evidence and compelling storytelling. However, the collection lacks a cohesive organizing framework, causing the essays to feel somewhat disconnected at times. Nevertheless, Solnit’s powerful voice and unique perspective make this an essential read for those interested in contemporary feminist thought and activism.

Reflective annotations

Reflective annotations go a step further by discussing how a particular source fits into the broader context of the research project or how it has influenced the writer’s understanding of the topic. This annotation type requires the writer to critically engage with the source and articulate its personal or intellectual significance.

Reflective annotation example

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Haraway’s seminal essay has been instrumental in shaping my understanding of the politics of knowledge production. Her critique of the myth of “objectivity” in scientific discourse has pushed me to adopt a more reflexive and situated approach to my research. Haraway’s concept of the “god trick” – the presumption of a view from nowhere that claims universal, impartial knowledge – has been especially helpful in interrogating the power dynamics that underlie traditional academic knowledge frameworks.

As I grapple with questions of methodology and epistemology in my work on environmental justice, Haraway’s insistence on the partiality and embodiment of all knowledge claims has encouraged me to center the voices and perspectives of marginalized communities. This article has expanded my theoretical toolbox and inspired me to be more accountable and transparent about my positionality and its influence on the research process. Engaging with Haraway’s powerful and provocative ideas will undoubtedly continue to shape the trajectory of my scholarly journey.

Finding sources for your annotated bibliography

Ensure the sources you select are directly relevant to your topic or research question. This will ensure the sources are useful for your project. Otherwise, the assignment’s specific requirements and the topic you’ve chosen will guide the type of sources you should seek out.

Here are some tips for finding reliable sources for an annotated bibliography:

- Use academic databases and search engines: Start using academic databases and search engines such as Google Scholar, JSTOR, Project MUSE, or those provided by your school’s library. These resources are more likely to provide scholarly and peer-reviewed sources.

- Check for peer-reviewed sources: Look for sources that have been peer-reviewed or published in reputable academic journals or books. Peer-reviewed sources have undergone a rigorous review process, ensuring their quality and credibility.

- Evaluate the author’s credentials: Consider the author’s expertise, affiliation, and qualifications. Sources written by researchers, professors, or experts in the field are generally more reliable than those written by unknown or unqualified authors.

- Use recent sources: Unless your research specifically requires historical sources, aim for recent publications (within the last 5-10 years) to ensure the information is up-to-date and relevant.

- Consult primary sources: Depending on your research topic, primary sources such as original research studies, historical documents, or first-hand accounts can be valuable additions to your annotated bibliography.

- Check for citations and references: Evaluate the sources cited by the authors you are considering. If they have used reputable and relevant sources, it can be an indicator of the quality of their work.

- Verify the publisher: Look for sources published by reputable academic publishers, university presses, or well-known organizations.

- Seek recommendations: Ask your professor, librarian, or colleagues for recommendations on reliable sources or databases in your field of study.